In Sunshine, director Antoinette Jadaone trades the comfort of cinematic compromise for the blade of truth, delivering one of the most unapologetic and emotionally devastating portraits of young Filipina womanhood in recent memory.

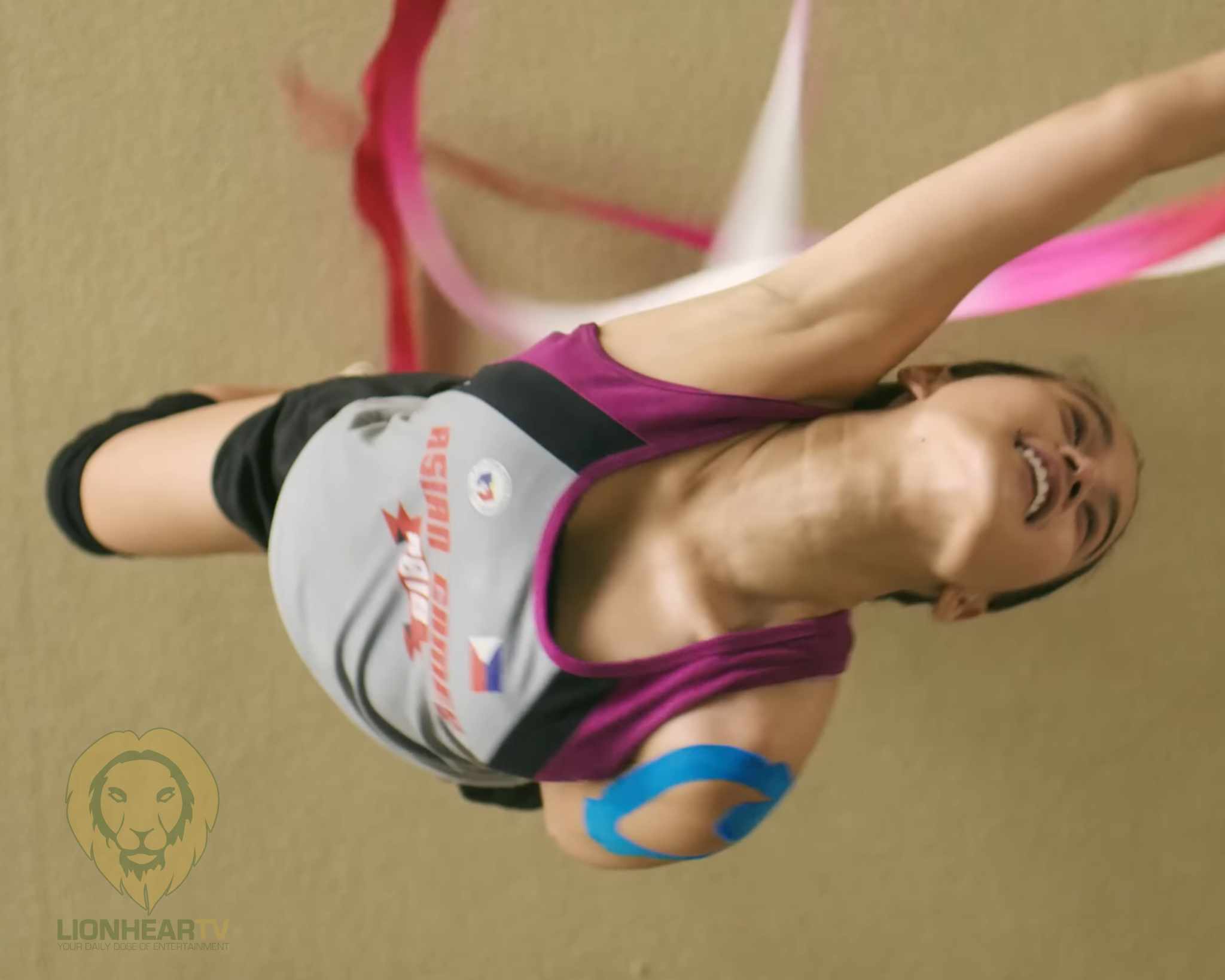

Maris Racal, in a performance that transcends acting and enters the realm of reckoning, portrays Sunshine—a teenage Olympic gymnastics hopeful whose life is upended by a single test strip and an empty promise.

Racal’s Sunshine is a girl teetering on the edge of adulthood, ambition, and annihilation. She twirls with the discipline of a champion, but when she learns she is pregnant—with the child of a pastor’s son who offers nothing but shame and P5,000 hush money—her spiral begins. And it is not the loud, cathartic kind. It is the slow bleed: across Quiapo’s alleyways, neon motel rooms, and the suffocating silence of Catholic homes where abortion is a sin and teen mothers sleep beside rosaries and regret.

Elijah Canlas, as the indifferent boyfriend whose polished demeanor conceals cowardice, punctuates the patriarchy with alarming precision. His cold line—“Alam mo na ang gagawin diyan”—is not just dialogue; it is a curse, echoing through centuries of erased accountability.

What Sunshine understands—and what Jadaone directs with razor clarity—is that reproductive health in the Philippines is not a right. It is a privilege wrapped in bureaucracy and cloaked in hypocrisy. The film does not sermonize. It stares. Sunshine’s journey is littered with contradictions: abortion pills sold behind candle stalls, holy men offering forgiveness instead of responsibility, and clinics where judgment arrives faster than help. In this landscape, the womb becomes a battlefield—and Racal holds the line.

Jadaone refuses neat endings, instead offering emotional honesty dressed as fantasy. The spectral friend (played by Annika Co), foul-mouthed and oddly tender, cradles Sunshine through the trauma with ghostlike compassion. It is this companion—imagined or real—that adds a layer of painful magic to the film’s climax. When Sunshine twirls in the finale, the ribbons slicing through air like blades of defiance, her imaginary friend reappears—not as a condemnation, but as a quiet “Gets ko na.” In that line, forgiveness is reframed—not as pardon from sin, but as understanding of impossible choice.

There are moments in Sunshine that will make you weep—not from pity, but recognition. The dark motel sobs, the rosary press against a belly too swollen to hide, the stare of a thirteen-year-old girl impregnated by her uncle—each scene is a mirror held up to a country that teaches women shame before sex education. Jennica Garcia, playing Sunshine’s sister, becomes the tender counterpoint: exhausted, resilient, and quietly revolutionary. Her love carries the film’s emotional center, a reminder that sometimes, survival is ceremony enough.

Sunshine is not just a critique of Catholic guilt or broken policy—it is a portrait of poverty. Jadaone frames Sunshine’s lack of choice not in morality but in economics. The rich fly abroad. The poor drink bleach. There is no real abstinence in homes with no doors, no safe sex in barangays with no clinics. And so Sunshine asks the question: Who gets to live, and who is simply expected to endure?

Maris Racal’s brilliance lies in her restraint. Her Sunshine is not dramatic; she is desperate, determined, broken, and brave. Racal lets her eyes do most of the work—carrying generations of buried pain and unfelt rage. For all the roles she’s played before, this performance cuts the deepest. Not because it is showy, but because it dares to be quiet in a world that prefers girls who smile through silence.

Sunshine is a love letter to the girls we fail, a memorial to the choices we strip away, and a reminder that sometimes, grace is simply choosing yourself—blood, bruises, and all.

Rating: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐